A little about my process...

In the beginning phases of my dissertation, I knew I wanted a diverse collection of works represented: contemporary, old, unconventional, but most importantly, works that are extraordinary and works that are neglected. My initial parameters for selecting compositions were based on two main factors: the quality of the work and my own personal programming decisions.

I knew that I wanted to represent as many living women as possible, highlighting those which I deem most worthy for which to advocate, and choosing those compositions which I feel represent them the best, and required that each living composer had to be making a living from the sales of her compositions, and/or through teaching composition at a higher educational institution. Even after reaching this level of success, I wanted to choose women that I felt were still undervalued and underrepresented, even if this was the case only because they were still in the beginning phases of their careers. Those included who are just starting their careers consist of mostly younger composers, like Tonia Ko, born in 1988, and the youngest composer included, although not always, as is the case with Franghiz Ali-Zadeh, born in 1947.

Franghiz Ali-Zadeh (b.1947)

While it was important to me to represent as many living women as possible, I also included seven composers from past generations whom I feel are undervalued or underperformed: Franziska Lebrun, Maria Theresia von Paradis, Emilie Mayer, Pauline Viardot-Garcia, Luise Adolpha Le Beau, Amy Beach, and Lili Boulanger. The oldest work in this dissertation is by Franziska Lebrun (her Sonata op. 1 No. 3 in FM was composed in 1780) whereas 8 compositions represented throughout the recitals were composed in the last decade.

My parameters for instrumentation were only that of size and authenticity from the original work. I often find that works composed for larger orchestrations generally don’t work well with a reduced piano accompaniment, especially with more contemporary works. This meant no concerti would be included. So I focused my research on pieces for solo violin or smaller chamber ensembles, the work for string quartet by Caroline Shaw, Entr’acte, being the piece with the most performers.

I also wanted to explore works which experimented with different sound worlds than the conventional instrumentation, and discovered such an abundant number of works in this realm that I focused my third and final recital around this theme of various instrumentations and sound worlds. Franziska Lebrun’s Sonata began the final recital. I really would have preferred to perform this Sonata on Baroque violin with fortepiano, but the fortepiano could not be tuned down for logistical issues, so I settled for using my modern violin with a Baroque bow and playing in a more Baroque style. I also suspected the fortepiano was a great way to open the audience’s tastebuds before transitioning into Tonia Ko’s Still Life Crumbles which was scored for harpsichord and violin, and which really travels through different sound spectrums and explores the different possibilities of the sound relationship between the violin and harpsichord by using different stops.

While written for more standard instrumentation, Caroline Shaw’s Entr’acte and Gillian Whitehead’s Torua both employ unconventional extended techniques to expand the various sound worlds. And last but certainly not least, Sofia Gubaidulina’s Silenzio is an extraordinary example of a work that creates an entirely new universe with its relationship between the string instruments and the bayan, or in this case, the accordion.

When I was living in Switzerland a few years back I was fortunate enough to meet and briefly work with Sofia Gubaidulina while performing her St. John’s Passion. The work was entirely unlike anything I had come across and I fell completely in love with her extraordinary expression and unique vision. Her mere presence was exhilarating and she spoke with such conviction that I became a Gubaidulina enthusiast for life. That experience played a crucial role in my development as a musician, creative thinker, it gave me a new appreciation and perspective, and, without a doubt, played a role in leading me to choose this topic for my dissertation.

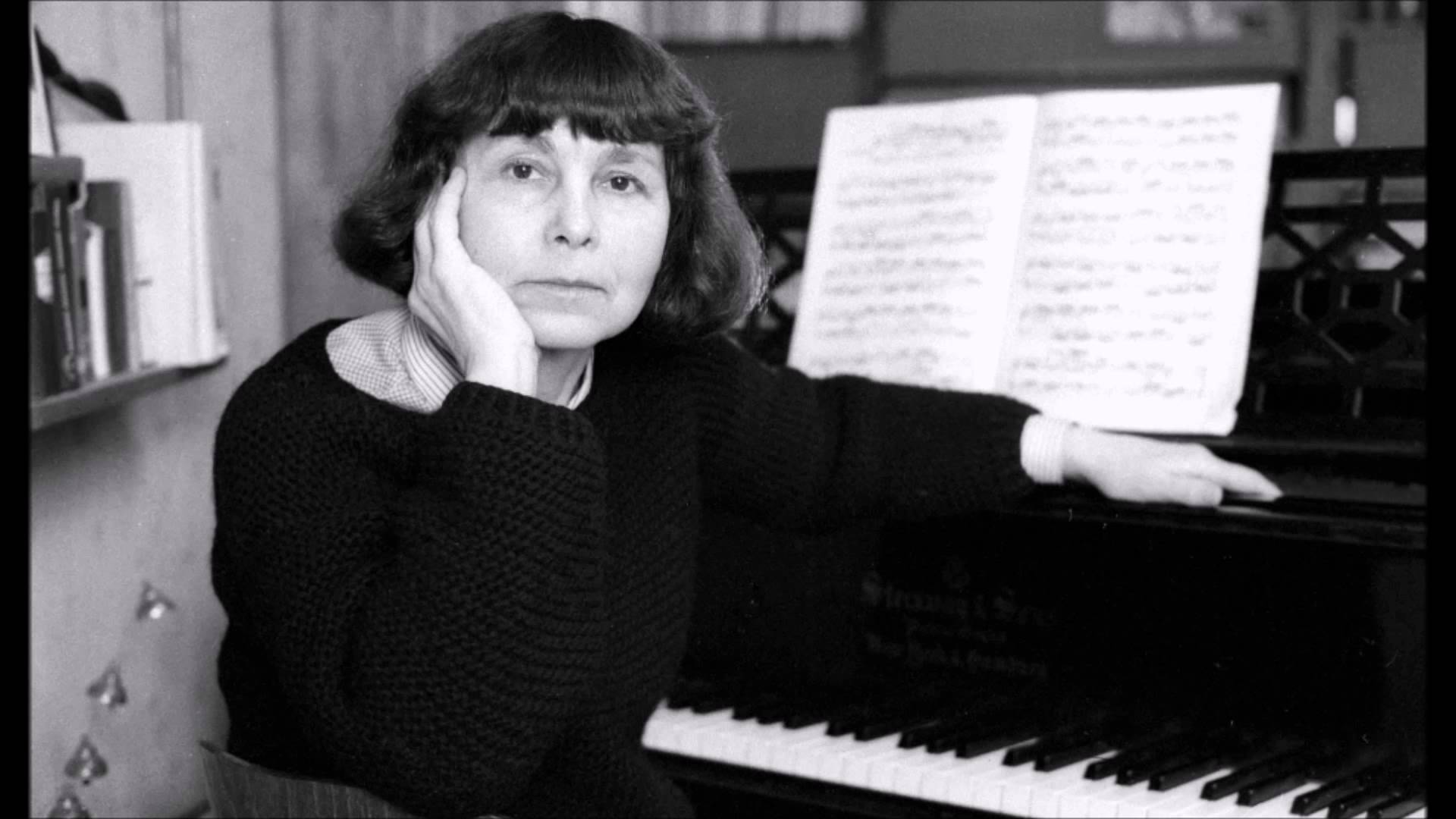

Sofia Gubaidulina (b.1931)

After compiling a list of remarkable compositions from which I could begin to program I began to notice parallels: among them - a theme of tonalities around the note ‘D,’ works which found inspiration from Bach, and an affinity for nature as a stimulus for creativity. I used these themes as a basis for my first recital.

The inspiration for Augusta Read Thomas’s Silent Moon for Violin and Cello, Joan Tower’s Big Sky, and Tina Davidson’s Blue Curve of the Earth all found their creation through nature. Missy Mazzoli’s work for solo violin, Dissolve, O My Heart, and Kaija Saariaho’s Frises were not only both directly influenced by Bach, they were influenced by the same work by Bach: his Partita in D Minor for solo violin. In addition to Thomas’, Mazzoli’s, and Saariaho’s works being based tonally around the note ‘D,’ the recital began with the first note played by the violin being a D, and concluded with the single held open D string on the violin, which ends Tina Davidson’s Blue Curve of the Earth.

The most important aspect for inclusion of a composition was that it was a work of the highest quality, a true work of merit in my opinion, to the point that it could speak for itself, while at the same time acting as a genuine expression and distinct representation of it’s creator.

This goes to the point of the slideshow’s as well. It was critical for me to not just present the works, but to present a distinct impression of the person who created the work. I displayed photographs of each composer while performing their pieces with the intention that it could bring a clearer portrayal and give the audience a better way to relate to each woman personally. As a performer or an audience member, I often find myself considerably more removed from works when I have no context of the composer as a person. The mere act of seeing her face immediately brings a closer relationship to the creator and creation.

Gabriela Lena Frank (b.1972)

For me, the three ‘main courses,’ so to speak, of the recitals, Gubaidulina’s Silenzio, Saariaho’s Frises, and Frank’s Sueños de Chambi, each give a very distinct impression of the composer. After performing these works I feel like I know each composer personally, as each woman exhibits a very earnest and sincere part of herself through the work.

I hope this project has also contributed to the available inspirational output and provided another platform for living women composers which will assist in furthering their careers.